What is Objective Optimism?

Note: This is the full-length, comprehensive articulation of Objective Optimism as a practical personal philosophy and framework for living. It is intended not as an easily consumable summary, but as a foundational essay that unpacks the full depth, structure, and implications of the method. This piece may be referenced, excerpted, or built upon in future writings, but it is meant to stand as the most complete version to date.

Introduction: A Rational Framework for Optimal Living

This framework is born from lived experience. It reflects the recurring patterns I’ve observed—in my own choices and in the lives of others. Again and again, I’ve found that every area of life improves to the extent that I apply this mindset, and falters to the extent that I stray from it.

Still, take this as a hypothesis, not a proclamation. The method itself demands continual refinement. As I take on new challenges—from others and myself—and as I live and learn, I revise and clarify. But this is, to date, the most comprehensive formulation I can offer.

The Reputation Problem: Why Optimism Needs Saving

Optimism has a PR problem. It's often mistaken for naivety, blind hope, or emotional immaturity. As John Stuart Mill once wrote:

“I have observed that not the man who hopes when others despair, but the man who despairs while others hope, is admired by a large class of persons as a sage.”

In today’s world, pessimism is often mistaken for depth. The cynic is respected; the optimist, suspected. Why?

Because there is such a thing as false optimism—a kind of cheerleading disconnected from facts. It borrows the aesthetic of strength while discarding the substance of clarity. And its prevalence has damaged the concept itself. When people hear “optimism,” they often think of delusion, denial, or ungrounded emotionalism.

But this cannot even properly be called optimism. I aim instead to define a version that is sober, grounded, and intensely practical. It is not blind to reality—it is guided by it. I call it Objective Optimism (OO).

Optimism as Optimization (Not Perfection)

In Objective Optimism, the term “optimism” is best understood through its root: to optimize. It’s not about wishing or pretending. It’s about seeking the best possible outcome—given reality as it is.

Optimism, in this framework, means engaging with the world to discover what can be improved, leveraged, or built upon. It’s the mental habit of asking: What is the most constructive path forward, given what I know and what I face?

But this does not mean chasing perfection.

In fact, perfectionism is anti-optimistic. It demands flawlessness—but because perfection is impossible (everything can always be improved upon), it sets an irrational and unreachable standard. This often leads to paralysis, self-doubt, or avoidance. OO, by contrast, embraces continuous improvement. It accepts that nothing will ever be perfect—and proceeds anyway.

Perfectionism tries to avoid errors. OO tries to create value. One gets stuck; the other moves.

The goal of OO is not to idealize life—but to optimize it.

What Is Objective Optimism?

Objective Optimism is a mental method—a disciplined orientation toward action and achievement. It combines two essential commitments:

Objectivity: The willingness to identify and integrate all relevant facts. To see clearly, without distortion or evasion.

Optimism: The focused effort to discover what can be done, built, or leveraged to achieve the best possible outcome—not in fantasy, but in fact.

OO is not a mood. It’s not positive thinking. It is not a belief that everything will work out regardless of cause. It is a rational, reality-oriented stance that begins with clarity and ends in constructive engagement.

It stands in contrast to two other mindsets:

Pessimism: A habitual focus on obstacles, risks, or reasons for failure.

Subjective “Optimism” (SO): A form of faux positivity that avoids hard truths in favor of feeling good.

On Subjective "Optimism” vs. Faux Positivity

I continue to use the term Subjective “Optimism” (SO) for structural comparison, but make no mistake: SO is not optimism at all. It is optimism in name only—a kind of emotional counterfeit. If anything, it is wishful thinking dressed up in smiles. It borrows optimism’s language while rejecting its foundation: reality.

(Note: In other contexts, I’ve referred to this mindset as “Faux Positivity”—a phrase that may better capture its performative cheer. For now, I’ll retain SO for conceptual consistency, especially in comparative tables and older references.)

Why Focus Matters: The Glass Half-Full Reconsidered

You’ve heard the metaphor: Is the glass half-empty or half-full?

The real insight is that both are true—those holding either perspective might be called a “realist.” The deeper question is: Which do you focus on?

OO is the consistent habit of focusing on what is present, usable, and empowering. It does not deny problems; it contextualizes them. It centers perception on what can be built, what remains in reach, and what progress is possible.

Pessimism fixates on limitation—on what’s missing or broken. Subjective “Optimism” ignores limitation entirely, glossing over it with unearned cheer.

Only OO sees reality as it is—and still chooses to engage.

The Three Levels of OO

Objective Optimism operates on three interrelated levels. Each reinforces the others, forming an integrated mindset that is situationally actionable, habitually cultivated, and philosophically grounded.

Situational (Tactical)

“In this moment, with these conditions, what can I do? What is the best result I can pursue?”

This is where OO most often begins: in the concrete here and now. It is the choice to respond constructively in the moment, identifying leverage points, resources, and actionable next steps—even in less-than-ideal circumstances. This level is about applied rationality in real time.

Cognitive (Strategic)

“How do I habitually relate to the world? What patterns of thought do I default to?”

Beyond isolated situations, OO becomes a strategic mindset—a mental posture trained over time. It is the habit of scanning for possibility, not out of denial, but from a rational commitment to action. Instead of reflexively fixating on limitations or threats, the cognitive optimist seeks the next viable move, the kernel of opportunity, the way forward.

Metaphysical (Foundational)

“What is my basic orientation toward existence itself? Do I see reality as navigable and life as worth pursuing?”

This is the deepest layer. At the metaphysical level, OO affirms that the world is intelligible, that cause and effect govern outcomes, and that success is possible to those who engage reality with clarity and purpose. This is not faith—it is not the belief that things will magically work out. It is the conviction, grounded in observation and experience, that reality can be known, and that within it, good can be achieved by effort.

Unlike Subjective “Optimism,” which drifts on wishful thinking, or religious faith, which invokes a benevolent providence, metaphysical OO begins with the sober recognition that reality is neutral—but navigable. Life is not guaranteed to be good, but it can be made good. The pursuit of flourishing is not futile—it is rational.

OO affirms, at every level, that flourishing is achievable—not guaranteed, but possible—when one engages reality honestly and acts deliberately.

Why This Distinction Matters

Much of the confusion surrounding optimism arises from shallow definitions. People conflate optimism with cheer, pessimism with insight, and passivity with realism—as if accepting futility were somehow more honest than striving. But these associations are false.

We must distinguish:

OO from pessimism

OO from Subjective “Optimism”

Rational confidence from blind faith

Reason from rationalization

This conceptual clarity matters—not just in theory, but in practice. Because how you think about your life determines how you live it.

These distinctions are further blurred by how loosely the terms are used in daily life. When someone says, “He’s optimistic about the game,” they usually mean he thinks his team will win. But optimism here simply refers to a positive prediction—not a mindset. A person may think he’s likely to lose and still be an optimist—if he’s actively doing everything he can to improve his chances. Likewise, someone may be labeled pessimistic for doubting a business proposal, even if his skepticism is grounded in careful analysis and long-term hope for success. These passing judgments tell us nothing about the person’s characteristic mindset. They reduce a deep orientation toward reality into a fleeting impression of mood or momentary appraisal.

You’re Not One Thing All the Time

A reasonable objection: “But I’m not just one of these all the time. I shift.”

Exactly. We all do. That’s the point. These categories aren’t labels for your identity—they are tools for your clarity. We all slip, unconsciously, into habits of thought that reflect pessimism or Subjective “Optimism.” But the goal is not to legitimize those mindsets as alternatives—it’s to recognize them for what they are, and to realign.

The purpose of the framework is not to offer a menu of acceptable options, but to draw sharp distinctions—so that you can identify the method you’re operating by in any moment and return to the one that works. OO is not a badge or a personality type. It’s a deliberate method. And it only works if you choose it—again and again.

Living It

To live with Objective Optimism is not to deny difficulty. It is to refuse distortion. It is to be:

Relentlessly honest about your context

Relentlessly focused on what you can do about it

Committed to building and growing, not lamenting or evading

This orientation reshapes your approach to setbacks. It reconfigures your goals. It changes how you relate to others—and to yourself.

Yes, it leads to better outcomes. But more than that, it leads to something deeper: alignment. You begin to trust yourself—not because you believe everything will be okay, but because you know you’re committed to engaging reality with clarity and purpose.

When you train your mind to see clearly and act accordingly, you stop waiting for life to grant you permission. You start shaping it.

That is the essence of Objective Optimism.

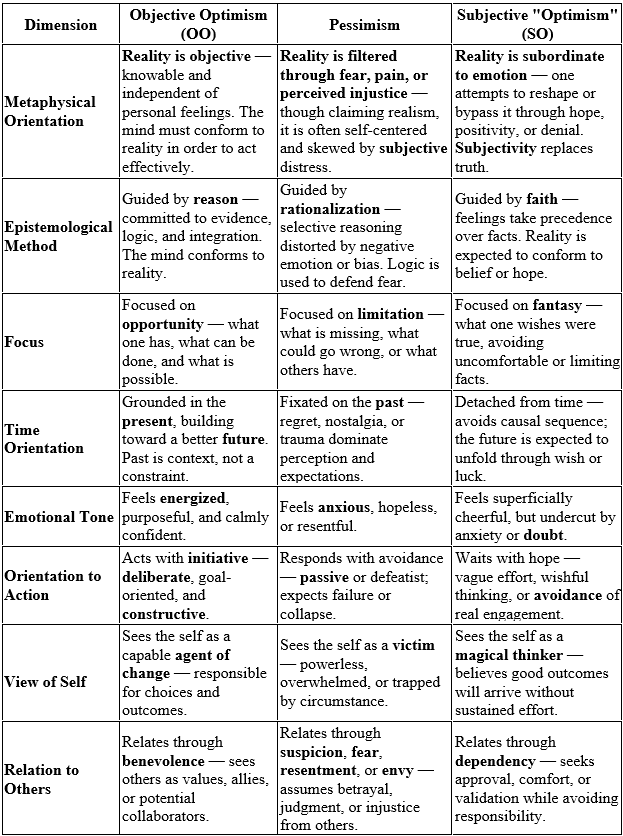

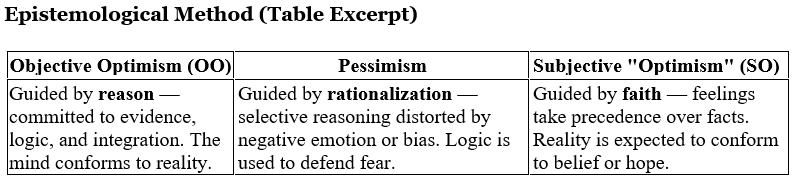

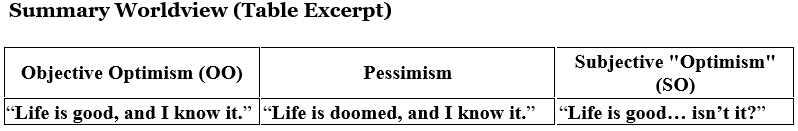

Comparative Table: OO vs. Pessimism vs. SO

Below is a condensed comparison of the three primary mindsets addressed in this framework. While no one is a pure representative of any one column, the point is to clarify the fundamental orientation and consequences of each, especially when applied consistently.

In the sections that follow, we’ll unpack each row of the table, illustrating how these mental methods operate in daily life—and why OO offers the most life-affirming path forward.

Breakdown of the Comparative Table

Each section below expands on a single dimension of the comparative table, offering rich insight into the distinctive orientations of Objective Optimism (OO), Pessimism, and Subjective "Optimism" (SO). These breakdowns serve to bridge the concise table summaries with the lived experience and philosophical depth behind each mindset.

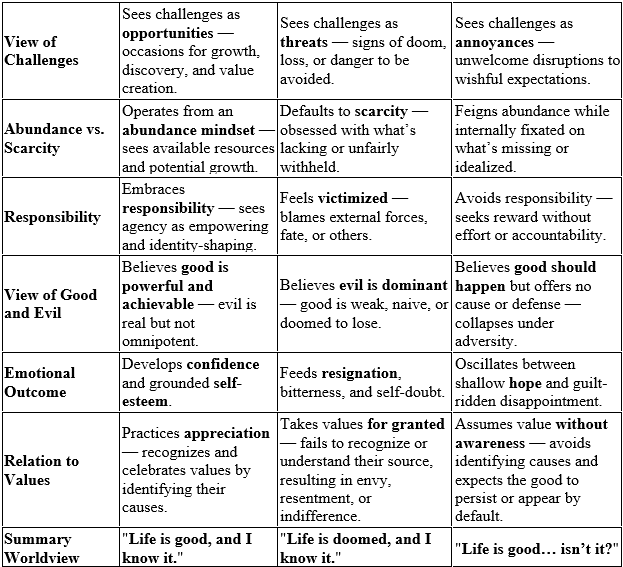

Metaphysical Orientation

Objective Optimism (OO): OO begins with the conviction that reality is objective—independent of one’s wishes, feelings, or fears—and that it can be known, engaged, and navigated. The world exists as it is, and the mind’s task is to grasp it, not reinvent or evade it. This orientation produces psychological solidity. The OO mindset doesn’t require illusions to function; it draws power from facing facts clearly and using them well. It sees existence not as an enemy to defeat nor a mystery to escape, but as a field of possibility.

Pessimism: Pessimism often masquerades as realism, but it is deeply colored by subjectivity. It views reality not as an objective context to navigate, but as a threatening arena filtered through pain, trauma, or fear. Its relationship to existence is distorted—sometimes through the lens of injustice, sometimes through helplessness, but always in a way that centers the perceiver's suffering as metaphysically primary. Even when claiming to be “factual,” the facts it sees are selectively chosen to reinforce a belief that life is cruel, dangerous, or hopeless.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO doesn’t attempt to confront reality at all—it attempts to override it. Its metaphysical posture is one of wishful primacy: the belief, often unspoken, that if I feel good, things will be good; that the universe somehow conforms to my hope. This is subjectivism in its purest form: the substitution of emotion for fact. Rather than engaging with the world as it is, SO reshapes its perception to soothe itself. But this comfort is fragile. Reality eventually reasserts itself, and without tools to engage it, the SO mindset collapses into confusion or despair.

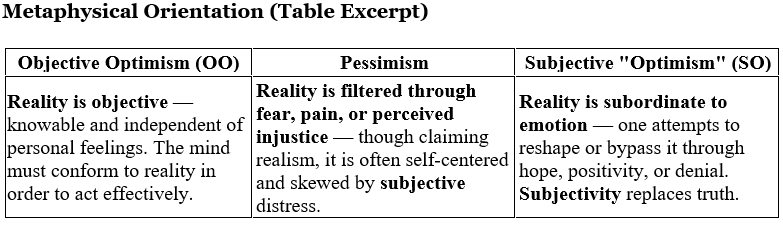

Epistemological Method

Objective Optimism (OO): OO is grounded in reason—an unwavering commitment to logic, evidence, and integration. It approaches thought as a method of discovering what is true and useful. Reason, in this context, isn’t cold or abstract. It is the disciplined lens through which reality becomes navigable. This mindset fosters mental clarity, long-range coherence, and the confidence to act even amid uncertainty.

Pessimism: Pessimism does not lack intelligence—it distorts it. It uses rationalization, not reason. Rationalization is the selective use of logic to defend fear, doubt, or resentment. It masquerades as thoughtfulness while quietly evading the burden of objectivity. The pessimist marshals facts not to discover truth but to reinforce despair. The result is a kind of defensive intelligence—clever, often convincing, but ultimately crippling.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO relies on faith—not religious faith, necessarily, but a kind of emotional absolutism. It takes feelings as primary and treats them as truth. Logic becomes secondary, or disappears altogether. Facts that challenge comfort are dismissed, minimized, or reinterpreted. This leads to a mindset that feels peaceful until it is tested—at which point it lacks the cognitive tools to adapt.

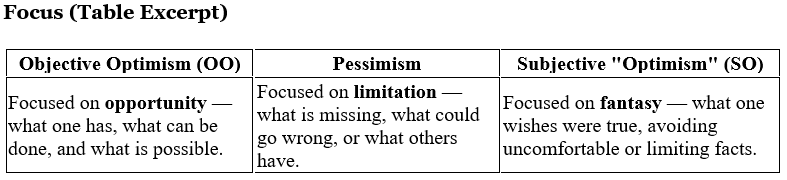

Focus

Objective Optimism (OO): OO orients its attention toward opportunity. Not naïve cheer, but a constant inquiry: What’s possible here? What can be improved, learned, or created? This focus produces motion—it initiates action and fuels perseverance. Even in hardship, OO seeks leverage points. Its attention is purposeful, directed at value.

Pessimism: The pessimist focuses on limitation—what’s wrong, missing, broken, or unfair. Their gaze is consumed by obstacles. Even in moments of relative calm, they scan for the next collapse. This fixation narrows imagination, blocks joy, and justifies inaction. It says: What’s the point?

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO tries to avoid pain by shifting focus to fantasy. It substitutes imagined ease for real potential. It affirms the positive, but without specificity. This is not goal-setting—it is wishful drift. SO says things will “just work out,” and then avoids the effort of making it so. In doing so, it abandons real opportunity in favor of vague hope.

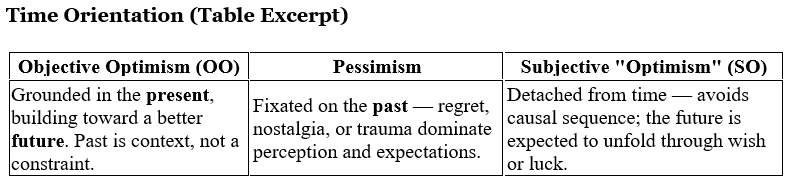

Time Orientation

Objective Optimism (OO): OO inhabits the present while building toward a future. It treats time as a continuum of opportunity—where today’s choices shape tomorrow’s outcomes. The past is acknowledged, learned from, and integrated, but not allowed to dominate. This orientation allows for growth, healing, and creative action. OO’s relationship to time is causal: actions now have consequences later, and that’s a source of power.

Pessimism: Pessimism is anchored in the past. It treats past pain, failure, or injustice as the defining truth of reality. Even nostalgia, which might appear warm or wistful, becomes a kind of refuge—an attempt to relive a time when life felt safer or more certain. The pessimist clings to “better days,” not just as memories, but as a substitute for present action. Time is not a path but a weight. The future is expected to echo the worst of the past. Because causality is seen through a lens of defeat, planning feels futile, and risk feels reckless.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO floats above time. It avoids the burden of the past and the effort required by the future. It hopes things will improve but without a causal bridge. The past is dismissed or romanticized; the future is expected to deliver on hope alone. This mindset often resists responsibility because time, for SO, is not a tool—it’s a backdrop. Without a firm grasp of cause and effect, motivation becomes mood-driven and progress remains elusive.

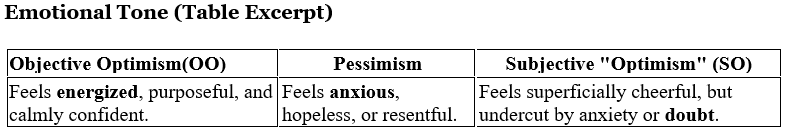

Emotional Tone

Objective Optimism (OO): The emotional tone of OO is earned confidence. It stems from coherence between one’s values, perceptions, and actions. The OO individual feels energized not because everything is easy, but because effort feels meaningful. Calmness doesn’t mean indifference—it means clarity. A life oriented toward growth, grounded in reality, and guided by reason gives rise to authentic joy and resilience.

Pessimism: Pessimism breeds emotional weight. There is an ambient sadness, bitterness, or resignation that colors experience. Because the pessimist expects hardship, they live braced against it. Even good moments feel suspicious—like the eye of the storm. This emotional tone becomes self-fulfilling: fear leads to withdrawal, which reinforces isolation, which deepens despair.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO feels light—until it doesn’t. Its cheerfulness is often performative, a posture of positivity that masks inner doubt. When things are going well, SO rides high. But that high is unearned, and therefore unstable. The emotional collapse can be sharp: disappointment feels like betrayal, and hardship feels like existential threat. Without a grounded reason to trust oneself, emotional fragility becomes the norm.

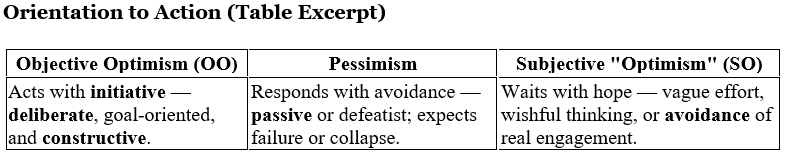

Orientation to Action

Objective Optimism (OO): OO translates vision into motion. It embraces purposeful, goal-directed effort—not frantic doing for its own sake, but action tethered to value. This mindset sees agency as essential to human nature. To act is to shape reality. Even small steps feel empowering because they align thought with movement. OO does not wait for conditions to be perfect—it begins, adjusts, and perseveres.

Pessimism: Pessimism paralyzes. Its actions, when taken, are often reactive or resigned. Since the future is feared or doubted, why act? Effort feels futile. This creates a vicious loop: inaction reinforces helplessness, which deepens the sense that nothing can be done. When pessimists do act, it is often with low expectation and minimal commitment—just enough to say they tried.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO delays meaningful action. It substitutes affirmations or vague plans for real engagement. Effort is often superficial—more about feeling productive than achieving results. Action is reactive to mood, not guided by principle. When things don’t go as hoped, SO tends to collapse or blame circumstances. Without a deliberate approach, hope becomes a kind of avoidance—something that replaces action rather than fuels it.

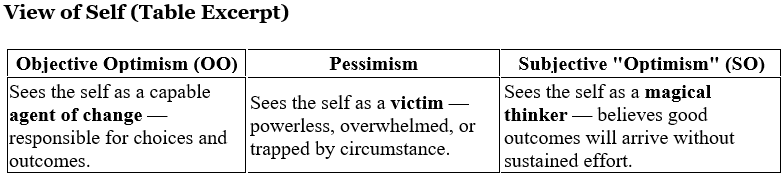

View of Self

Objective Optimism (OO): The OO mindset regards the self as an active agent in shaping outcomes. It recognizes that one's choices, habits, and thinking directly influence results—and that this is a source of power, not pressure. This sense of agency fuels responsibility, growth, and earned pride. Believing in oneself doesn’t mean expecting perfection; it means trusting that through honest engagement and continual improvement, one can move toward flourishing.

Pessimism: Pessimism casts the self as fundamentally at the mercy of forces beyond control—society, luck, history, biology. It sees effort as insufficient and identity as burdened. This self-image breeds apathy or bitterness. Since the self is seen as inherently limited, attempts at growth often feel performative or doomed. Confidence gives way to self-doubt, and eventually, to self-neglect.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO tends to inflate self-image without grounding it in achievement. It feels deserving of success, love, or joy without understanding what sustains those things. This mindset often avoids rigorous self-examination—it prefers to feel good rather than grow strong. Without confronting limitations or identifying areas for development, the SO self becomes brittle: outwardly positive, inwardly insecure. When challenges arise, this fragile self-concept can shatter.

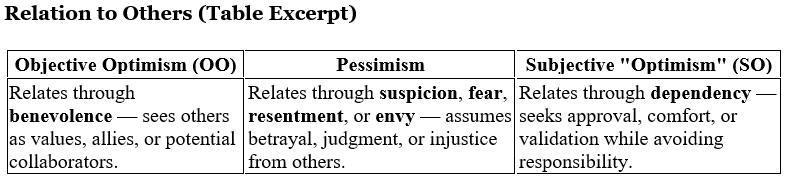

Relation to Others

Objective Optimism (OO): OO sees others as potential collaborators, partners, or fellow value-creators. There is an essential benevolence—a conviction that others can be good, that shared goals are possible, and that one’s success does not depend on others’ failure. This outlook encourages genuine connection. It motivates curiosity, trust, and even admiration. OO does not require blind trust or naivety; it simply begins with the premise that others, like oneself, are capable of reason and value-oriented action. This makes generosity, celebration, and cooperation possible.

Pessimism: Pessimism sees others as dangerous, indifferent, or out to get you. People are competitors, threats, or burdens. Even when interacting with “good” people, the pessimist waits for the shoe to drop. This orientation produces suspicion, envy, resentment, or withdrawal. Since the pessimist believes life is stacked against them, others’ successes feel like evidence of injustice—or reminders of their own failure. It’s hard to build deep friendships or lasting alliances from that stance. It’s harder still to find joy in another’s gain.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO relates to others through dependency. People are not partners in mutual exchange but emotional safety nets—sources of praise, comfort, or validation. SO can seem generous or affectionate, but it struggles with boundaries, accountability, or respect. The relationship must feel good, not necessarily be good. This leads to fragility: criticism feels like betrayal, and independence feels like rejection. Relationships, rather than being chosen and earned, become a buffer against reality.

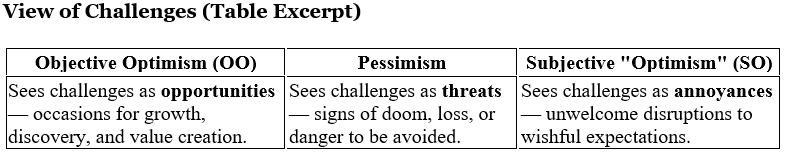

View of Challenges

Objective Optimism (OO): OO sees challenges not as interruptions, but as integral to the process of growth. Difficulties are data points. They reveal weakness, clarify values, and test commitment. A challenge is a call to rise, to learn, to adapt. This does not mean OO romanticizes pain—but it does reject avoidance. It asks, “What can be gained from this?” and in so doing, makes challenge serve progress.

Pessimism: To the pessimist, challenges confirm what they’ve long suspected: life is hard, success is rare, and effort is often wasted. Each setback feels like another nail in the coffin of hope. Challenges are not seen as opportunities to learn, but as proof of futility. This breeds caution, paralysis, and cynicism. Even small problems take on epic proportions. The emotional and mental bandwidth required to persevere is spent anticipating the next blow.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO finds challenges inconvenient. They puncture the fantasy. Because SO often avoids difficult truths and expects ease, it feels shocked or disoriented when things go wrong. Its positivity isn’t built to withstand resistance. This makes challenges feel unfair or disheartening—not because they’re objectively overwhelming, but because SO hasn’t built the mindset to face them. Rather than rallying, SO often retreats into distraction or denial.

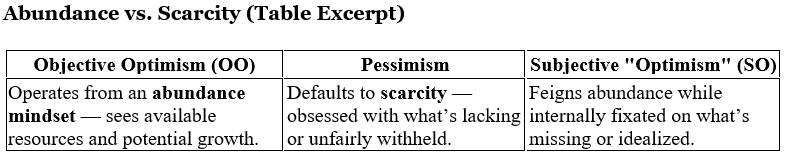

Abundance vs. Scarcity

Objective Optimism (OO): OO views the world as rich in potential. It begins with the conviction that there is value to be found, created, and expanded—if one chooses to look for it. Abundance doesn’t mean having everything; it means seeing the possibility of more through effort, connection, or learning. This mindset energizes innovation and generosity. Even in moments of lack, OO searches for leverage, resourcefulness, and forward motion.

Pessimism: Pessimism operates from a zero-sum premise: for one to win, another must lose. Resources are scarce, opportunities are rigged, and time is slipping away. This scarcity mindset makes fulfillment feel unreachable. It breeds envy, resentment, and hoarding—of time, energy, affection. Rather than activating effort, it stifles it: Why try, when there’s never enough?

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO talks like abundance but lives like scarcity. It repeats affirmations and embraces “positivity,” but often avoids the real work of generating value. It expects the good to arrive—somehow—while sidestepping the causal steps that make it so. SO may claim to “manifest” wealth or love, but deep down, it feels uncertain, even anxious. When results don’t appear, its optimism collapses into blame or doubt.

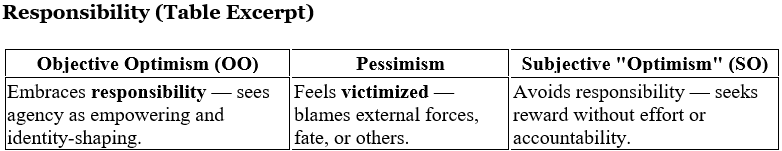

Responsibility

Objective Optimism (OO): Responsibility, for OO, is not a burden—it’s a privilege. To be responsible is to be capable of response. It means seeing one’s choices as causal and meaningful. This mindset encourages ownership: of time, thoughts, relationships, and outcomes. Responsibility becomes the ground of self-respect. When things go well, the OO individual knows why. When things go wrong, they look inward before blaming outward. This orientation fosters resilience and personal evolution.

Pessimism: Pessimism externalizes control. The world is unfair, rigged, or too broken to fix. Responsibility feels like punishment—a demand placed on someone already overwhelmed. The pessimist sees themselves as a victim of circumstance. This belief, once entrenched, saps initiative. Blame becomes a defense mechanism, but also a cage. As long as someone else is at fault, one’s own power remains inaccessible.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO sidesteps responsibility by clinging to wishful thinking. It hopes for good things without committing to the work they require. When results don’t appear, SO blames fate, vibes, or vague external forces. Responsibility is seen as stressful or joy-killing. This detachment may preserve short-term comfort, but it sabotages long-term fulfillment. Without a sense of ownership, the SO individual can’t fully claim their wins—or grow from their failures.

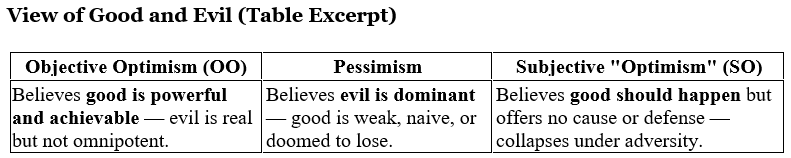

View of Good and Evil

Objective Optimism (OO): OO holds that the good is real, attainable, and worth fighting for. It recognizes the presence of evil but does not grant it metaphysical superiority. This view empowers moral clarity: one can choose the good, align with it, and see its effects in the world. Evil exists, but it is the exception, not the rule—and it can be overcome through reason, courage, and principled action.

Pessimism: Pessimism tends to see evil as the prevailing force. Corruption, cruelty, and decay are seen as inevitable. Goodness is fragile at best, foolish at worst. This view corrodes motivation to act morally or idealistically—it feels like a setup for heartbreak. Over time, pessimism undermines any confidence in justice or redemption. Evil wins not only because it acts, but because pessimism surrenders.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO assumes the good should prevail—but it doesn’t know how. It avoids confronting evil because doing so would disrupt its hopeful narrative. SO may believe in “good vibes” or karmic justice, but without grounding these ideas in causal mechanisms, it has no defense when confronted by real injustice or pain. It freezes, flees, or denies. In the face of evil, SO’s optimism folds—because it was never prepared to resist.

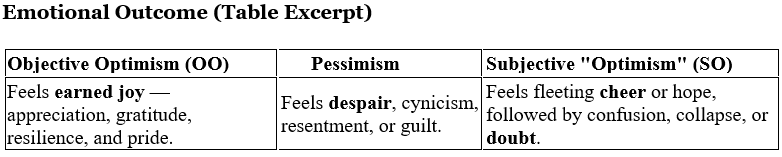

Emotional Outcome

Objective Optimism (OO): OO culminates in earned joy. Its emotional tone is not random, but the natural reward of a rational, reality-oriented mindset. When one sees values clearly, pursues them honestly, and integrates experience coherently, the emotional result is confidence, appreciation, and pride. Even setbacks are framed constructively—they fuel growth, not collapse. This leads to emotional resilience. OO enables joy not as a momentary high, but as a durable sense of meaning and momentum.

Pessimism: Pessimism produces the emotions it fears. In expecting failure, it invites disengagement and isolation. The result is often a mixture of despair, cynicism, or guilt. Even when good things happen, the pessimist questions their legitimacy or permanence. Joy feels undeserved or unsafe. Over time, pessimism builds emotional calluses—protecting the self by numbing it. What begins as caution becomes resignation.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO aims to feel good—but without stable foundations, its emotions are fragile. It may feel cheerful, hopeful, or confident when things go well, but these highs are often hollow. Because SO hasn’t built an integrated, causal understanding of why good things happen, it struggles to process setbacks. Disappointment becomes destabilizing. The collapse into doubt or despair can feel sudden and total. Without understanding, there is no emotional continuity—just fluctuation.

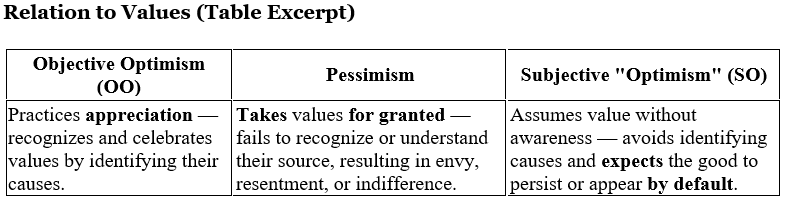

Relation to Values (Appreciation)

Objective Optimism (OO): Appreciation is not just an emotional bonus—it is a cognitive act. The OO mindset identifies values clearly and integrates their causes. It knows why something is good, how it came to be, and what sustains it. This causal awareness makes enjoyment possible. When you know how something was earned, built, or nurtured, your gratitude is real. It isn’t hollow or performative. Appreciation, then, becomes a direct path to sustained emotional reward.

Pessimism: The pessimist often experiences what others would call blessings or advantages—but cannot enjoy them. Because they do not pause to identify causes, or because they assume what they have is insufficient or unfairly distributed, their experience of the good is corrupted. They take value for granted and push happiness into the future. A silent refrain underlies their psychology: “I’ll be happy when…” But this projected fulfillment never arrives—because they’ve never learned to appreciate the good they already have. Without that habit, even future gains will fail to register as meaningful. Resentment often follows. Why should they have this and I don’t? Or worse: Why does any of it matter? Without appreciation, even legitimate value feels meaningless.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): SO imagines it is appreciating life—but without identifying causes, there is no real appreciation, only assumption. The SO mindset believes the good should simply be there. It clings to outcomes while ignoring effort. This makes enjoyment fragile and fleeting. When things go well, SO smiles. But it doesn’t understand why, so it can’t trust it. And when the good falters or fades, there is no resilience, only confusion or collapse.

Appreciation is the bridge between achievement and emotional reward. Without it, happiness becomes impossible—because the good can never fully register. OO trains you not only to achieve, but to see and feel what you've achieved. That is the essence of fulfillment.

Summary Worldview

The final row of the table captures the essential emotional and philosophical orientation of each mindset in a single sentence. While condensed, these statements are not simplistic—they reveal how each worldview filters experience and directs one’s relationship to existence.

Objective Optimism (OO): “Life is good, and I know it.” This is a statement of earned clarity. It doesn’t mean that life is always easy, or that hardship never arises. It means that life, in its essence, is worth engaging—that reality is navigable, that values are attainable, and that joy is possible. This is not blind affirmation; it is a conclusion grounded in causal understanding and principled living.

Pessimism: “Life is doomed, and I know it.” This is the outlook of finality. It sees effort as futile and goodness as ephemeral. Even when beauty or success appears, it’s dismissed as fleeting or suspect. The underlying belief is that the game is rigged—or worse, that meaning itself is a lie. The result is resignation, cynicism, or detachment. It’s not that pessimism always feels bad; it’s that it believes the bad is more real than the good.

Subjective "Optimism" (SO): “Life is good… isn’t it?” SO longs for reassurance. It craves the feeling of goodness without the structure to support it. It whispers hopeful slogans and clings to feel-good narratives, but it lacks the epistemological grounding or moral confidence to truly know. As long as everything feels right, it floats. But without roots, the first gust of reality can topple its fragile hope.

Synthesis: The Core of Objective Optimism

Objective Optimism is not a mood. It’s not a hope, a cheer, or a strategy of denial. It is a method—a commitment to seeing the world as it is, and choosing to act in alignment with what can be achieved. It rejects both the fatalism of pessimism and the fantasy of superficial positivity. Instead, it roots your life in reality—then dares you to build something beautiful from it.

To live with Objective Optimism is to take yourself seriously—as a thinker, a creator, a moral agent. You accept the facts, not to surrender to them, but to transcend them. You act not out of fear or blind hope, but out of rational clarity and a desire to flourish.

OO in Practice: Real-World Scenarios

Consider a career setback. The pessimist sees confirmation of worthlessness. The SO clings to hope that it will “work itself out.” OO evaluates, adjusts, and moves forward with purpose.

Or in a strained relationship: the pessimist assumes betrayal; the SO avoids conflict and hopes for harmony. OO confronts the truth, owns responsibility, and works toward mutual growth.

But it’s not just the big moments. OO lives in the daily: the decision to get out of bed with intent, to approach your work with focus, to bring clarity to a conversation, to reflect instead of deflect. That’s what it means to live well—not waiting for some grand reward, but finding dignity in the structure of your choices.

Meaning and Optimization in Daily Life

OO doesn’t promise ease—it promises meaning. It sees life not as a state to coast through, but as a structure to shape. Your effort matters. Your mind matters. Your days matter—not because someone says so, but because you can see so.

To optimize your life is not to chase perfection. It’s to bring your whole self—your reason, your will, your vision—to the ordinary: breakfast, work, exercise, relationships, reflection. All of it becomes the canvas for deliberate living.

That’s what OO does: it brings you back to the present—and gives you the tools to make the most of it.

Enter at Optimism

The idea for this framework crystalized during a final exam panel discussion in one of my classes. I wasn’t on the panel—I was moderating while my students led the conversation. At one point, a student posed a deceptively simple question to the group:

Does optimism come from success, or does success come from optimism?

That question lingered. Because I’ve seen what happens when success comes before clarity—it doesn’t build confidence; it breeds doubt. When you don’t know why something worked, you can’t trust that it will work again. That’s when fear creeps in. You start to wonder if it was luck—or worse, a fluke you can’t repeat.

Confidence, by contrast, comes from understanding. From method. From a mindset that aligns with reality and knows how to engage it.

That moment in the classroom helped me name something I had long practiced but never fully defined. Not false positivity. Not blind hope. But Objective Optimism—a method for moving through the world with clarity, constructiveness, and courage.

This is the architecture of the Virtuous Cycle: A clear, reality-facing mindset → deliberate action → real results → earned confidence → deeper clarity.

So the real question becomes: where can one enter the cycle?

You can’t start with outcomes. You can’t wait for confidence to arrive by accident. You have to begin with the orientation that makes all the rest possible.

Most people try to enter through the Success Door. But that door only opens after you've proven you know how to walk through it.

The real entrance is elsewhere.

It’s not predetermined that some are optimists and others are not. The choice is always available—to enter at optimism.

Not through blind faith, but through the rational decision to engage with reality as it is—and with yourself as you can become.

Because that’s the only way to make it yours.